The fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989, and German reunification 329 days later, were undoubtedly for me the clearest expression of American power I have ever experienced. Deutsche Textversion

My encounters with, and interest in, American power began in my childhood. I still clearly remember the moment when, as a young boy, I first became aware of the immense power of the United States. Not power in the sense of the peace, freedom and prosperity enjoyed in the happy suburbs of America—no, power in the sense of the American ability to „convince“ or “persuade” other nations to do what the United States wants.

American Power as Military Power in World War II

My father was a physicist, so I spent many summers of my childhood in Los Alamos, New Mexico. One of my first memories is the fascinating exhibition at the Bradbury Science Museum of the Los Alamos National Laboratory. Right at the entrance was a display board with sand fused to glass and impressive black and white photos. One was from a tower with a spherical bomb on top, another from an enormous mushroom cloud.

The Los Alamos physicists, my parents read, had ignited their „gadget“ at 5:29 a.m. on July 16, 1945, in the desert near Alamogordo, New Mexico. Their „Trinity Test“ unleashed the explosive force of twenty thousand tons of TNT, producing heat like on the surface of the sun; a shock wave that could flatten cities; and a strange radioactivity: toxic, invisible, long-lived. More importantly, with the atomic bombing of the Japanese cities Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945, the United States ended World War II very much in its favor. The “Bomb” allowed the isolationist United States to make commitments it otherwise would not have. So began the Atomic Age, with all its mysterious and nefarious consequences.

My curiosity was aroused. At the age of five I had found a new hobby. There, in Los Alamos, the scientists had made a power I could barely fathom. I wanted to know more.

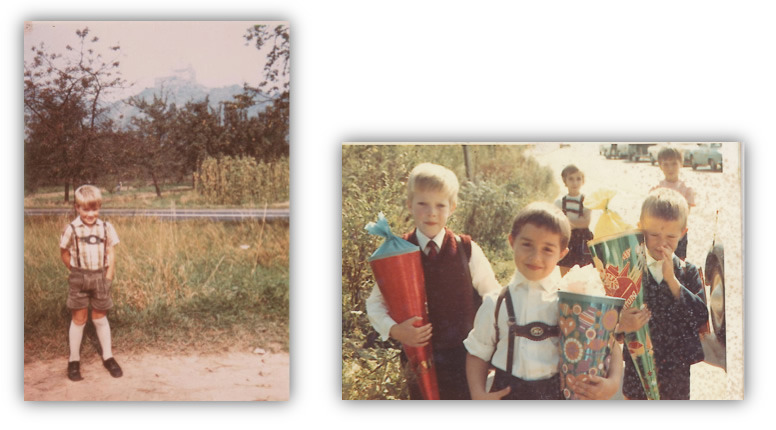

After this summer in Los Alamos, my family moved in fall of 1967 for two years to Heidelberg, Germany. I fell in love with this fabulous country, the knights’ castles and the ruins. The Heidelberg Castle showed the effects of battle up close. A tremendous force had blown open the thick stone walls of the half-standing powder tower. Everywhere, my imagination saw the knights and their armor, the cannonades against the fortress walls. German kindergarten and first grade “Einschulung” left the boy from Laramie, Wyoming, proudly wearing his Lederhosen, thinking German life was a wonderful fairy tale.

One day, there in Heidelberg, I saw my dad reading a very thick book. Over 1000 pages. There was a strange symbol on the front of this book. I began to draw it with pretty, colorful German felt-tip pens. My dad saw this and said loudly: „Stop it immediately!” I didn’t understand what he meant—until he told me the story of this book, William Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich—and why I should not draw the swastika. My dad had a lot to tell because I couldn’t get enough. I had never heard such a story. The American GIs, so my understanding, had saved the good Germans from the evil Hitler. I was captured. Fairy tales no longer interested me. History was the real story.

Today, I still see the Second World War as the measure of all things. In the outcome of the Second World War lies the genesis and nature of today’s world order. Vietnam and Watergate corrupted American power, like many other mistakes, whether in Afghanistan, Iraq or the White House. But with its unique geography, economy, and people, together with the atom bomb and its United Nations allies, the United States could win the Second World War and gain a global position of power that endures. With victory in World War II, and the ensuing relationship with Germany’s Europe and Japan’s Asia, the United States became a global superpower without historical or contemporary parallel, in a world that will long be shaped by the consequences of the Second World War.

Back on the high prairie of Wyoming, my love for Europe remained, as did my curiosity about European history. In 1978, a decade after our first visit, my family returned to Europe, this time to Zurich for a year. I was 16, more man than boy, and most delighted to be back in the land of fairy tales. There was a lot going on in Zurich, in Europe and in the world. There were revolutions in Nicaragua and Iran. The Cold War was back, not in Vietnam, but in Europe. Détente and Ostpolitik were in trouble. The threat of the new Soviet nuclear weapons, mounted on mobile SS-20 missiles, dominated the headlines. Despite my newly found love for Europe, I returned to the United States, now a senior in high school.

Mutual destruction because of Europe?

Graduating in the summer of 1980, I decided to study International Studies at the University of Wyoming. At the same time, I joined the National Guard. Four months of training at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, left me a combat-ready carpenter and engineer providing base maintenance to Camp Guernsey, a popular artillery range set in the curving canyons and high escarpments of the North Platte River valley. The U.S. Army paid for a good part of my studies. As a student of international relations and a soldier in the reserve, I was combining the theoretical and the practical.

While I was in U.S. Army basic training, the self-styled „Cold Warrior“ Ronald Reagan defeated Jimmy Carter in the 1980 presidential race. Reagan promised to re-arm the United States to deter and contain Soviet „adventurism.” He expanded America’s nuclear arsenal. In addition to new cruise and Pershing missiles for Europe, Reagan won funding for new land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles, each equipped with ten nuclear weapons, the so-called MX, to be stationed in the prairie of Wyoming.

Back from basic training and taking international relations classes, I began to wonder. Why does the United States need so many new nuclear weapons if a nuclear war would mean mutual destruction anyway? Wasn’t that overdoing it a bit? Then I learned about American nuclear strategy. At the time, so the argument, superiority in nuclear weapons was important. Without superiority, the Soviets might question the credibility of the U.S. nuclear shield for the allies in Europe, especially the Federal Republic of Germany. This strategy and these weapons would show that the US would not shy away from defending the NATO allies (including West Berlin) from a Soviet invasion—even if it meant using the missiles sitting in their silos on the Wyoming prairie.

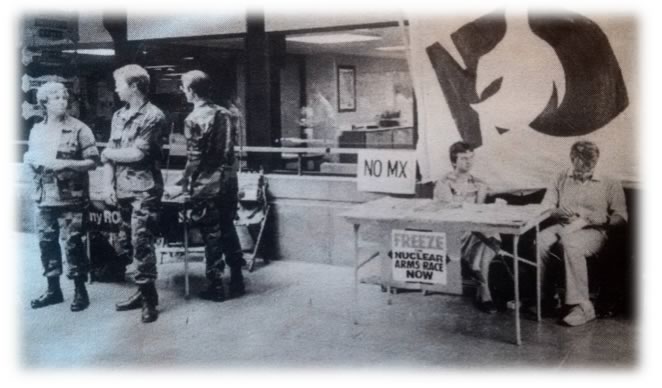

As a young student and soldier, I quickly came to the conclusion that it would be better if the Germans and the other Europeans would do more for their own defense–so that the United States would not have to provide this expensive and yet not entirely credible nuclear guarantee. I began to attend the Nuclear Freeze Movement meetings, where I also argued that it would be easier to freeze the growth of the U.S. arsenal if Europeans did more for their own defense. I felt at home in the embracing arms of the peace movement. It was there that I met my future wife, Ursula Kölsch, an exchange student from Hamburg, living on a horse ranch. Foreign affairs took on a whole new and wonderful meaning.

Soon Ursula and I started to take a more active role in the Freeze Campaign. With her help, I became chairman of the Wyoming Nuclear Weapons Freeze Coalition for all of Wyoming, and was asked to represent our state and its 500,000 inhabitants in Washington at the National Freeze Committee. At the same time, I served as a delegate to the Wyoming State Democratic Convention—as a one-issue, “Stop-the-nuclear-arms-race!” political activist.

Having completed my undergraduate degree, I wanted to continue my studies in Europe, convinced that Europe was the solution to the MX missile problem in Wyoming (and that studying in Hamburg with Ursula would be great fun). What might reduce the danger of nuclear war? What might persuade Europeans to do more for their own defense? Were there any possibilities for disarmament? With these questions, I entered a master’s degree program at the University of Hamburg, wanting to write about conventional arms control and disarmament in Europe. It seemed to me that a European military balance was key to freeing the United States from its risky commitment to use nuclear weapons first in the defense of Europe.

At a time when the Cold War seemed increasingly dangerous, Mikhail Gorbachev took power in the Kremlin. He realized how wrecked the Soviet system was, how incapable the Communist colossus was of competing with the West in high technology. He bet on reconciliation and reform, Glasnost and Perestroika.

The escalating Cold War also provoked a reaction in the West. Many American and European observers saw the U.S. as financially overburdened, geostrategically overstretched, and at risk of decline and fall like all the empires before. Paul Kennedy’s The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers became a bestseller in 1988. The British historian warned that the USA was facing imperial overstretch. In that same year, having finished my master’s degree in Hamburg, I decided to pursue a doctorate in European Studies in Washington, DC. I wanted to write my dissertation with David Calleo, of the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), who had just published the book, Beyond American Hegemony: The Future of the Western Alliance. The book was a call on Europe to assume more burdens and show more solidarity, so that the United States could wind down its Cold War engagement and invest more at home. I was on board.

The Disarmament of History – The Fall of the Berlin Wall and Victory without War

At SAIS, we thought Europe should do more to stand up to the Soviets. We did not think that it would be the Poles who did the standing up, yet on June 4 and 18, 1989, the citizens of Poland voted freely—as Polish protesters against the Communist government had demanded. Solidarity, the opposition movement leading the protests, won a majority and formed a non-communist government under Tadeusz Mazowiecki. Gorbachev’s Moscow just watched. In letting the Poles go, the Soviet leaders made it easier for Europeans to live up to the American call for burden-sharing. Gorbachev offered disarmament and the unfathomable possibility that the Red Army would largely depart the Warsaw Pact states of Soviet-subjected Eastern Europe. Unlike his predecessors, Gorbachev was serious.

Forty-five years after the end of the war, the General Secretary of the Communist Party and head of the Soviet Government, Mikhail Gorbachev, realized that a military buffer zone in Eastern Europe was costing the Soviet Union more than it was worth. In good Russian tradition, he ordered a strategic retreat. Gorbachev’s concessions surprised everyone. Noble Peace Prize winter and Time Magazine’s Man of the Decade, he showed that individual leaders can make a difference—if they know which way the wind is blowing. It is astonishing that the Western alliance showed itself flexible enough to respond to Gorbachev’s radical new proposals, to work (hard) with him and his people to overcome the Cold War division of Europe.

While diplomats from NATO and the Warsaw Pact negotiated the withdrawal of the Red Army from Eastern and Central Europe, political developments accelerated. Once released, there was no restraining the desire for freedom, the rush to travel to the West, the rejection of the ruling regimes. In Hungary, Czechoslovakia, then East Germany, Bulgaria and Romania, the communist parties crumbled. The Red Army did not intervene, as in Prague ‘68, Budapest ‘56, or East Berlin ‘53.

This desire for freedom showed itself not only in Europe, but also in China. In June 1989, demonstrators gathered at Tiananmen Square in Beijing, also demanding freedom. Soon there were hundreds of thousands, also gathered around a large, statue-of-liberty-like, Goddess of Liberty, until June 4. On this day, the first day of the Polish elections, the Chinese military cleared the square using machine guns and tanks. Western sources suspect that thousands of demonstrators died.

As the Monday demonstrations in Leipzig grew in the fall of 1989, many feared a „Tiananmen solution“ would descend upon East Germany. Mikhail Gorbachev, attending the 40th anniversary celebrations of communist East Germany’s founding on October 7th, warned that „dangers await only those who do not react to life.“

The rulers in East Berlin realized they could expect no support from Moscow. They began to give in. The power of the people, the power of the streets, driven by the desire to be free, to travel, was beyond their capacity to control.

The East German Communist Party (SED) was imploding. Three weeks after the resignation of Head of State and Communist Party General Secretary, Eric Honecker—on the evening of November 9, 1989, SED Politburo member Günter Schabowski, while sorting through a stack of papers at press conference, read aloud (perhaps unintentionally) from a memorandum, the following historic sentence. „Permanent departure can take place via all border crossing points of the GDR to the FRG or to Berlin West.”

Huge crowds flooded toward the crossings, crying with joy, cheering and singing, peacefully walking, if not running from East to West Berlin. No shots were fired. The border guards smiled and held roses. Through the Wall the East Berliners went, the Wall that had seemed so impermeable for so long—since the 13th of August 1961, when East German border guards put up the first barriers, strung the first barbed wire, made the Iron Curtain real.

On November 9th, I was in Washington, supposedly busy with my dissertation on the „European Dilemmas of the SPD“—but the daily news from Europe was too distracting to me and my fellow students. We all knew what was at stake: People rising up in East Germany had always been seen as the way a Third World War would start. Instead, the people danced on the Wall. No mushroom clouds, just popping champagne corks. Everything stayed peaceful. The contest between the American Dream and the Real-Existing Socialism was coming to an end. Gloria Steinem, famed American feminist, summed it up well. “It was the first feminist revolution. There was no violence. And then everyone went shopping.” The West was winning, and the Red Army stayed in its barracks. The supposedly irresolvable East-West conflict was resolved, not by force of arms, but by the force of the people and their dreams of a better life. Who would have expected this after the European tragedies of the 20th century?

Spurred on by the pace of events, diplomats from the four victorious powers and the two German states quickly negotiated the reorganization of Germany and Europe. 329 days after the fall of the Berlin Wall, and 45 years after the end of the Second World War, the Federal Republic of Germany secured a final settlement of World War II with the international community’s approval of the annexation of East Germany and the continued membership of this larger, largely reunited Germany in the NATO Alliance.

All over Europe, the ruling communist parties lost their power. The same fate awaited the Soviet Union. A failed coup d’état against Mikhail Gorbachev in August 1991 ended the Communist Party’s control of the Soviet Union, thus leading to the end of the Soviet Union, which formerly broke up into Russia and fifteen newly independent states on December 31st, 1991.

Such a radical and surprising change in the balance of power is rare in history; that it was so peaceful is more than a miracle. The iconic image of the dancing crowd on the Wall remains a fitting conclusion to a bloody 20th Century.

The Power of Human Dignity

In some respects, there was more at stake in the Cold War than there was in World War II. A third, nuclear, world war would have resulted in incomparably more human deaths. In this nuclear stalemate, caution and restraint were paramount. As such, superior military technology and alliances were important, but not sufficient. Victory in Europe would only come with the desire of the people to escape Soviet tyranny—and the exhaustion of the apparatchiks that ran that tyranny. In wanting to be prosperous and free of the corrupt communist bureaucrat, they changed the international balance of power. This desire for a different kind of government, this quest for human dignity had enormous geostrategic consequences. Here, as the Federal Republic’s first chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, had hoped, was the West exerting its “magnetic effect” – not only because of its military superiority, which is of limited use in the nuclear age, but also because of its image of human dignity and its ability to balance freedom with the ownership of property and the rule of law.

The United States and its allies won the nuclear stalemate against the Soviet war economy with the opening of the Berlin Wall. The same power that brought about peaceful victory in the Cold War destines the United States to remain the only superpower. In the 21st century, a world government is more likely than a China, or India, or Russia, or Europe as the next superpower. If mankind is spared a nuclear war, the United States will continue to stand astride the world stage like no other, still benefiting from the same advantages that led to victory in the First World War, the Second World War and the Cold War.

Today’s peaceful European order, with a united Germany at its center, is both a sign and a pillar of American power. Without the United States as a European power, there would be neither a European peace nor a secure America. But together, if not always on an equal footing, the USA and Europe are unbeatable. The fall of the Berlin Wall and reunification of Germany reflect the complementary power of Europe and the United States like no other event. The basis for cooperation, for the sharing of burdens and benefits across the Atlantic, this dispensation of power, has its critics, whether in Beijing, Moscow, Tehran, Europe, or the United States. Real alternatives to America’s role in the Peace of Europe and the Peace of Asia are harder to find.

Thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, 75 years after the end of World War II, I live well and gladly in today’s Germany, in the romantic Rhineland, in a small village, grateful for a German capital in Berlin, which presents itself more as Rhenish than Prussian or Soviet: Slightly foolish, but pluralistic and committed to “Westbindung als Staatsräson,” as the Rhinelander, Konrad Adenauer, the first Chancellor of the post-war Federal Republic, would have wanted. Germany has achieved much in partnership with the United States, and I remain confident that Germany and the United States will continue their amazing success story.